Growing up, my late father told me that I was “born to move”. When I was born, the doctor who caught me almost dropped me because I was squirming so much. I am still fond of that story, because it is undoubtedly true. To me, it was normal to have an abundance of energy, as if everyone else in the world had that energy. It was my special super power where I felt confident and happy to move how I wanted to; I always felt a release and sense of calm after movement, exercise or stretching. It was a small moment in time in between life, where my brain shut off, and the chatter would cease to exist.

Skip forward to thirty-eight years later where I was given a late-stage diagnosis of combined ADHD. A light bulb went off in my brain; it all made sense; hyperactivity, hyper focus, the lack of impulse control, the inability to organize, simple tasks that I hated to do like cleaning and dishes, lack of focus while listening to podcasts or watching a movie and, lastly what most affects me is emotional regulation. It became an upwards battle, being stubborn and not wanting to think I was different or that something was “wrong with me,” it took a while to realize that something needed attention.

I was starting to have trouble with managing anxiety; crying at every stress, not focusing at work and not being able to manage daily life. It was also a period in my life where I was processing the trauma that I experienced at the age of thirteen when I saw my mother die due to cancer treatments. I have read several books about trauma and the nervous system, searching for answers to figure out why I reacted so strongly to life’s events, changes and social interactions (always with a nervous energy). It wasn’t until I started looking into ADHD that it all fell into place. Through my research about trauma, I discovered that neurodivergent brains already have a sensitive nervous system and find it harder to respond to stress. In my case, I got overstimulated and burnt out. Mixed with trauma, it is what I like to call a Neuro- F**** roller coaster.

Looking back, when I was a teenager, lacking one primary care giver and not knowing about ADHD, it was not surprising that I found an outlet to manage my symptoms. I loved running, weight training, dance and really any movement to help calm my system. Eventually, it lead to jobs and careers in the fitness industry and to my current job as a Registered Massage Therapist and Mobility Specialist.

The ADHD diagnosis has helped to clarify how my brain works and made me feel less ashamed. It created an in depth body awareness and deep learning about how the body-mind deals with stress and to find therapeutic ways to manage. I had always tried so hard to function and pushed myself to perform big accomplishments in order to seem normal, when really, I didn’t know what was going on.

It wasn’t until I was maybe thirty- five to thirty -eight, when my hormones started to change, that my ADHD symptoms skyrocketed. So here I am now in my fourth month of taking medications to help manage my symptoms, and life is quite different! I am more attentive, I have less burn out, I don’t need to run for hours to just get a dopamine hit, at work I am more present and I feel more motivated to do the hobbies that I love.

I think it’s important to understand that medication will not solve everything but it will give you the tools to function better and have better relationships, less burnt out and more focus in your career. The one area that I still struggle with a little bit is during my monthly cycle when hormones fluctuate. As estrogen rises and falls so does attention and focus - all the different chemical reactions and neurotransmitters sometimes becomes muddled. It has not been officially diagnosed but I am pretty sure that I display symptoms of PMDD; Pre- Menstral Dysphoria, basically a mood disorder and a sensitive system to changes in neurochemicals. Yikes!

At first I was angry that ADHD was not brought to my attention sooner, since it does run in my family and is genetic. It was comforting that my sister Anya, brought to my attention that our parents loved us children and they accepted that their daughter had high energy. I felt that had I known about the ADHD I could have navigated life better, but learning acceptance and compassion has been a big lesson and made me have a deeper understanding of myself and the world (its OK to rest!) - perhaps that’s why I am a good massage therapist.

ADHD, in my opinion, is a gift and can be harnessed to do so many wonderful pursuits. My favourite aspect about having hyper focus is that you can be engrossed in what you love to do; reading fantasy and history books for hours, hiking or running in the forest, deep conversations with friends and family. Even though it is hard to feel the stressors and difficult emotions you also feel the good emotions and it encompasses your whole body.

Luckily, there are foods, supplements and lifestyle changes that have been wonderful. Managing stress is a huge component, finding ways to ground oneself is crucial. Below I have complied a list of strategies that have been helpful to me. I like to pull out each one based on my needs. I understand that each person is unique and has different needs; my intention is to provide an example of the resources I have used in order help others.

Therapy

I have seen many therapists of the years, from counsellors to psychotherapists, and found that a therapist with training in Brain Spotting is very helpful to help process and heal traumatic events. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is also beneficial when it comes to using your brain from a top down process to logically state the reality of a scenario. However, I found that I needed something deeper that helped my brain to process trauma. Brain Spotting is a brain- body therapy that uses eye positions to help process trauma, stress and emotional blockages. With the idea that where you look affects how you feel and trauma gets stuck in the visual field. Brain spotting session’s create peace and changes the way you perceive that event and therefore creates healing.

Yoga Nidra

Yoga Nidra, or Yoga Sleep is the practice of introspection with a guide. There are several ways this yoga practice works; you can lye down or sit in chair, there is a guided voice talking to you. Using breathe, or sensing the breathe, gentle movement, sensory or somatic movements, visual meditation, and gaining introspection; body awareness. It is a state of mind between wakefulness and sleep, enabling one to be fully present.

Exercise and Yoga

I have always loved running, swimming or cardio based exercises. It allows me to rest my brain, and focus on what is happening in the moment. Repetitive movement has especially been helpful since it focuses on the task at hand. Especially if its outside in nature.

Yoga is very therapeutic since it’s a whole body movement that use the breathe and to move with intention and flow. Yin yoga, Vinyasa Flow and Restorative are some of my favourites.

Dancing

I have taken several forms of dance; from Belly Dancing to the basics of Break Dancing and Contemporary Dance. Dance opens up different ways of moving, it involves coordination, spacial awareness and the music make’s you feel free to “shake it off”.

Weight Training

My first full-time career was working as a Personal Trainer and Group Fitness Instructor. I really enjoy strength training. I think mixing cardio and strength training is the way to go for full-body health. Steady strength training with gradual increases in weight brings confidence and creates self-worth. The added bonus of strength training, especially lower-body strength, is important for cognitive health.

Hobbies

As for hobbies, I enjoy making art collages; using a variety of mediums from magazines to fabrics, paint, parts of jewellery etc. It allows me to escape for a while. Writing stories is fun and I enjoy the research part of creating a story; or you can just sit down and write about whatever comes to your mind! Colouring books creates mindfulness by focusing on the item you are working on. Most recently, I got back into collecting Lego sets (mostly Harry Potter) and building book nooks. These allow a steady focus and challenges the brain to follow instructions while you immerse yourself in creating other worlds.

Health Professional Support

Registered Massage Therapy; Indie Head Massage, Deep Tissue, Sports, Fascial Stretching

Osteopath; Visceral Manipulation

Pelvic Floor Physiotherapy

Books and Videos

Scattered Minds, Gabor Mate

The Woman’s Brain Book: Neuroscience of Health, Hormones and Happiness

Sarah Mckay

Krista Gansterer

RMT

CSEP PT®

Kinstretch®

Yoga Teacher

Many of us ADHDers have heard about the analogy that our brain is a Ferrari with bicycle breaks created by Dr. Hallowell. And while I respect him and understand that this is only an analogy and that ADHD is not easily defined, as a car enthusiast, I beg to differ.

If we are going to use a car to describe the ADHD brain it’s definitely not a refined Ferrari but more like an old muscle car, inefficient brakes, ridiculously overpowered, and essentially the suspension of a horse wagon.

As an ADHDer you are behind the wheel of a car that just doesn’t want to turn enough when you need to turn (understeer = decision paralysis) and that when you step on the gas a little harder its back slides out and spin more than you want (oversteer = impulsivity).

So you have to compensate for those errors all the time… ALL. THE. TIME.

Every millisecond you are trying to use it to navigate life, you are calculating, predicting, correcting, correcting the correction, screaming for dear life (rejection sensitivity), trying to remain behind the wheel, pulling yourself using said wheel as a handle rather than as a direction control instrument, all while experiencing a deep feeling of shame for being a worthless driver (self-discrepancy gap).

And it doesn’t stop there. The gas pedal sometimes gets stuck (hyperfocus), so good luck stopping, even if you had those Ferrari brakes. You have to learn the tricks that get it unstuck and pray that it works on time.

— Speaking of time, what time is it? — Said Inner Voice A

— Oops, we just blew through the red light on “I-should-go-to-sleep Street”! — Screamed Inner Voice B

— You truly are the worst driver! — Said yet another, Inner Voice C

— You are inept since we were kids and I feel unsafe, this is not going to end well — the voice continued.

— Anyway, that gas pedal is still stuck… — Voice A ignoring, as usual, Voice C

— What if we give a little skewed-to-the-right kick on the pedal to get it unstuck! — that was the always witty Inner Voice D, suddenly jumping in with a solution.

— Maybe — answered Voice A — but now that we are accelerating, “Very-important-deadline Avenue” is not that far so we might as well use the momentum to get there early… Can you guys imagine, everyone will love us.

— There!!! It worked, pedal unstuck!!! I save the day, again!!

— But what about “Very-Important-Deadline Avenue”? Well, I guess we can just keep going, and it would be heal… th… zzzzzzzzz —little did Voice A know that he was only human, the deadline wasn’t met. Alas, yes Hyperfocus is a superpower; but is an unreliable superpower really super?

Did I mention this muscle car is haunted? It is, a thousand voices inhabit the car. So it gets noisy.

The voices aren’t the only contributors to the noise, the radio turns itself on and sometimes it gets locked on, sometimes the tuner changes randomly.

Frankly it’s exhausting, so much that minivans look enviable in comparison: no surprises, comfortable, everything fits in there, not too fast or too slow, 360 camera view. The only problem is that, you know, it’s a minivan (I have nothing against minivans, in my old age I actually kind of like them).

I try to remind myself to keep driving and have fun doing it, embrace the challenge, embrace the muscle car, because I’m stuck with it but also because it can also be so, so FUN and interesting, charming, and cool.

If we just keep driving, exploring the tricks on how to tame it, taking care of it, servicing it properly; maybe, just maybe, we’ll get to glide through the highway with the full moon shining on that roof.

It will probably still scare the heck out of us, but we’ll laugh, put it back on gear and keep driving.

Turn it into a project car. Car lovers do not always like their cars but they are called car lovers for a reason. As much as they dislike walking up for a nice drive only to find a poodle of oil under their vehicle, they love to put in the time and effort to work on them, and then working some more on their dysfunctional, quirky, annoying project cars.

Get yourself a nice toolbox (like the CADDAC blog), read and get wrenching. You will never turn it into a fully self-driving minivan, but if you could, would you really want to?

May this help you when minivan people (god bless them, we know they mean well) complain about your “bad driving habits” and say things like: “If you really cared, you’d drive better!” or “Why didn’t you turn when you had to?!” May you remember this analogy then and may they understand that it is not a driving style, it’s a precision-driving act.

Keep wrenching, you are doing it fine!

Shaming has been the name of the game for kids with ADHD for a long time. I expect it became a problem at about the time mankind stopped living in the world and started trying to control it instead.

There was no need for children to behave like little adults until we started making them sit still for long periods of time at dining room tables, in church pews and in classrooms. At that point, the shaming of the neurodivergent began in earnest. This cartoon from the 1800’s typifies the treatment that ADHDers have been subjected to over the past few centuries.

Fidgety Phil

“Let me see if Phillip can Be a little gentleman; Let me see if he is able

To sit still for once at the table.” Thus, Papa bade Phil behave; And Mama looked very grave. But Fidgety Phil,

He won’t sit still; He wriggles, And giggles,

And then, I declare,

Swings backwards and forwards, And tilts up his chair,

Just like any rocking horse—“Philip! I am getting cross!” See the naughty, restless child

Growing still more rude and wild, Till his chair falls over quite.

~ by Heinrich Hoffman, 1809–1894

“Fidgety Phil” is thus labelled naughty, rude and wild. His behaviours, caused by the neurodivergence of which Phil has neither control nor understanding, become his personal flaws and deficiencies. The adults Phil interacts with continually remind, ridicule and punish him for his (perceived to be intentional) shortcomings and, before long, Phil will internalize these characteristics, believing himself to be all of the reprehensible things these responsible adults have told him he is. His guilt, shame and self-limiting beliefs will follow him throughout his life, becoming self-fulfilling prophecies. How much better are we doing now?

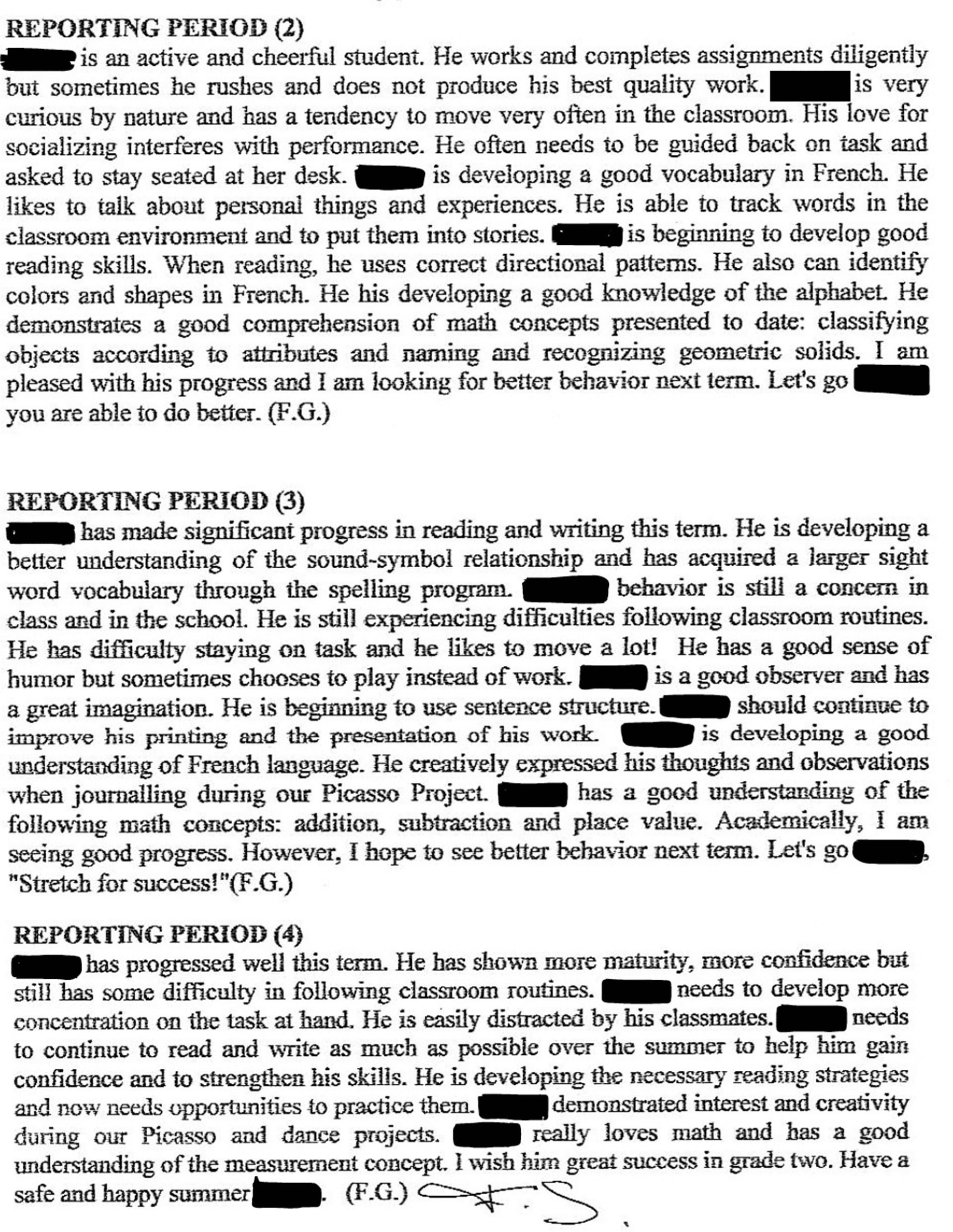

Following are comments found on a typical report card received by an extremely bright six-year-old boy with undiagnosed ADHD, either mixed or hyperactive type. Let’s call this little guy Phil!

The comments related to Phil’s abilities in reading, writing and arithmetic make him sound like the kind of kid who’ll be his high school valedictorian one day. In fact, Phil’s IQ is in the 150-160 range.

Unfortunately, all of the comments directed towards Phil’s behaviour foretell of a child whose academic accomplishments are likely to erode year after year to the point where graduating from high school at all will be a challenge. That is, in fact, Phil’s story.

Phil and children like him are chastised, report card after report card, year after year, for actions and behaviours over which they have no control. Over and over again they are told that they are not enough, that they:

Their teachers believe these things to be true. They also apparently believe that repeatedly telling kids like Phil that they:

Phil and others like him, both boys and girls, are punished further when they fail to correct their “bad behaviour” despite all of the painful judgements being directed at them about their character faults. This can take the form of detentions, extra homework, missing out on field trips, being kept inside during recess, having to clean the blackboards, having to sit at the front of the class or in a corner by themselves, all the way up to expulsion, which only adds to the trauma to which these kids are already being subjected. Not to mention the punishments,which may include physical punishments, they receive at home for all of their perceived failures at both home and school.

Take another look at Phil’s report card. His behavioural “problems” (Phil clearly exhibits some of the most common symptoms of ADHD) were mentioned some 20 times over the three paragraphs, appearing in two out of three lines on average.

Kids like Phil don’t just experience this level of trauma and public humiliation at report card time; they are subjected to it daily. They are told that they are “less than” multiple times most days over many, many years. Some experts estimate that, on average, by age 10, children with ADHD will have received a full 20,000 more negative messages about themselves than their neurotypical friends. The result is that many spend their lives believing themselves to be fundamentally and hopelessly flawed.

No amount of being belittled, chastised, singled out, punished, or even growing up, will transform a neurodivergent brain into a neurotypical one. Kids like Phil suffer ongoing trauma throughout their childhood when they should be being given the tools, therapies accommodations, and medications that would allow them to become the students everyone, including they themselves, want them to be.

Instead, unrelenting chastisement, ridicule and punishment means that many receive the gift of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) to go along with their ADHD. And having internalized these negative beliefs about themselves and what they are and are not capable of, they put self-limiting restraints on who they might otherwise have become.

Although Phil and others like him are likely to achieve much less in their lives and will have a much harder time negotiating their lives than what might have otherwise been the case, the Phils of this world often make it through life more or less in one piece.

Those with lower IQs tend not to fare as well. Research shows that an extraordinarily high percentage of people with ADHD become high school drop outs and/or teenaged parents, regularly lose their jobs, are often under employed, become substance abusers, have difficulty with relationships and money, spend time in prison, and the list goes on and on. They live difficult lives which either end violently or by suicide at equally alarming rates.

Is it any wonder that the life expectancy of people with ADHD is between 6 and 10 years less than that of a neurotypical person? With their self-worth dying by the infliction of thousands and thousands of tiny cuts daily, beginning far too soon in their young lives, how could it be otherwise? Surely, we can do better.

Many parents find themselves redefining what “home” means as their family changes and adult children start to fly the nest. When your family includes neurodivergent members—and when you’re working through decades of collected stuff—moving becomes its own unique adventure. If you’re thinking about downsizing or trying to declutter with ADHD loved ones, I hope our story makes you feel seen, understood, and maybe even gives you a little laugh amidst the chaos.

The Decision to Downsize

Our family includes two young adults, both with ADHD, who are now living in different cities and countries, each chasing their own dreams. My husband, also neurodivergent, was on a sabbatical, stepping away from his corporate role to embrace a very different, hands-on lifestyle. With the kids grown and this new chapter unfolding, it felt like the right time to start fresh and downsize.

Moving from a sprawling 3,000-square-foot house to a cozy 1,200-square-foot apartment sounded exciting on paper but was absolutely terrifying in reality. I knew that downsizing in midlife would be emotional, but I hadn’t fully anticipated how much our diverse neurological wiring— mine, my husband’s, and our kids’—would shape the entire experience.

Letting My Partner Take the Lead (Sort Of)

Since my husband was on a career break, he volunteered to plan and coordinate the move. I’ll admit I was skeptical. After 30+ years together, I know how many hobbies, gadgets, and collections he accumulates. He has ADHD and a not-so-secret love for stuff. Organization has never been his strong suit, especially when paired with his signature tendency to leave things to the last minute. But I decided to trust him and let go. I kept reminding myself of the lessons I’ve learned about appreciating different strengths in relationships and letting partners run their own process. He promised he’d get it done; I promised to trust him.

Reality Strikes: The Slow-Motion Five-Month Move

Five months passed. Progress was… minimal. Every time I expressed worry about our timeline, I was met with defensiveness, explanations, and a list of micro-achievements (“But look, I sorted the screws!”). Meanwhile, the to-donate pile barely shrank, and our moving deadline got closer and closer. Panic? Yes, mine was rising.

Our two children were home for the summer, each attached to their childhood treasures—games, photos, instruments, and bins upon bins of stuff. They sorted, slowly, though more often delayed by friends and the summer break. Sometimes it felt like I was living in a different reality from the rest of the family. Everyone else seemed unfazed.

“We’re Almost Done”—But Are We Really?

The closer the moving day, the more I started doubting my own expectations. Was I being too controlling? Was my “importance-focused” approach the only right way to handle this? When my family said, “We’re almost done,” was I missing something?

Like many ADHD families, I knew stress could spark bursts of energy… just rarely on my preferred schedule. My husband thrives on chaos and stress tolerance—qualities that sometimes make me want to scream.

The classic ADHD features—time blindness, poor time estimation, and the strong “I’ll do it myself” streak—were front and center. No matter how much I tried to step in, the answer was always the same: “It will get done.”

The Inevitable Last-Minute Race

Moving day showed up. Was everything packed? No. Were things sorted, donated, and labelled? Not quite. But somehow, through humour, creative problem-solving, and my husband’s legendary charm (which bought us an extension with the new owners), it all came together.

The boxes got stacked. Memories got sorted. Things still linger in storage, waiting for the “future us” to deal with them. Did it unfold the way I wanted? Absolutely not. But it worked—because creativity is our family’s superpower.

A moment for Reflection:

A New Chapter Begins

We’re settling into our smaller space. Some belongings will get sorted… eventually. What we’ve gained, though, is far more valuable: a reminder that brains, lives, and families don’t always roll neatly, but with enough love and adaptability, they’re always enough.

If you’re going through big changes with your neurodivergent family, know that your frustrations and laughter are both valid. Your path won’t look like anyone else’s—but it will be uniquely yours.

Here’s to embracing new beginnings, imperfect transitions, and the art of letting go, both of things and expectations!

I was diagnosed with ADHD a few months before going back to work after my second maternity leave. At the time, my daughters were just three years old and ten months.

When I got the diagnosis, it felt like everything suddenly clicked into place. All the things I’d quietly struggled with for years weren’t just personal failings; they were ADHD. And I wasn’t broken. I just didn’t know how my brain actually worked.

But more than relief, the diagnosis gave me clarity of purpose: If either of my daughters ever feels like I did, I want them to have tools, support, and self-understanding early - not years of internal shame.

Not long after my diagnosis, my mom dropped off a binder full of old report cards. I sat on the floor flipping through them. With ADHD in mind, they read completely differently.

“Audrey would have received an A if she had only handed in the project.”

“Audrey is easily distracted by her friends and needs to stay on task.”

“Audrey is a confident speaker and passionate about topics that interest her, but struggles when it comes to tests”

I remember loving school - especially plays, speeches, and anything creative. But I also remember the pit in my stomach before tests. The last-minute scrambles. The mental exhaustion from trying to keep up. I wasn’t lazy or careless. I just didn’t know what I needed, and neither did anyone else.

Getting diagnosed with ADHD as a parent is... a lot. You’re managing meltdowns and making lunches while also trying to unlearn decades of shame and figure out new ways to function.

I’m still in it. I’m still learning. But I’ve already made some changes that I hope add up to something my girls will carry with them. Even if they don’t have ADHD, I want them to grow up in a house where it's safe to be who they are, and where struggling doesn’t mean you're failing.

We talk about how everyone’s brain works a little differently, and that’s okay. Some people need more quiet, more breaks, or more reminders. Some people need to move, or rest, or pause and come back. I say things like, “My brain feels scrambled,” or “I’m feeling overstimulated and need a few quiet minutes.” And together, we are reading books like In My Heart by Jo Witek to help name our emotions from the day.

I try to normalize it all - not in a performative way, just as part of how we move through the day. I want my girls to grow up believing that having needs isn’t bad or something to apologize for; it’s just human.

I’ve tried so many of the “perfect routines” people post online, but they just don’t work for my brain - so I’ve stopped forcing it.

Now, it’s about reducing friction wherever I can:

Little things that make life smoother are a big win for me.

I forget things. I overcommit. I sometimes hit my limit and realize it too late. But I’m learning to ask for help and reset without guilt.

Sometimes that means tagging my husband in on a task I thought I could handle. Sometimes it means canceling a playdate. Sometimes it’s pizza for dinner…again. And I’m working on not apologizing for those choices.

What I want my girls to remember is this:

You can be capable and still need support.

You can be loving and still need rest.

You can be strong and still ask for help.

If either of my daughters ever struggles to focus, forgets something important, or feels like they’re falling behind, I don’t want them to jump straight to shame. I want them to feel seen and supported. I want them to know their worth doesn’t depend on performance, and that struggling isn’t the same as failing.

I’m doing this so they never have to wonder if they’re too much or not enough. So they grow up seeing what it looks like to understand yourself and meet that understanding with compassion.

If you’re figuring this out while raising kids, I see you. It’s a lot. But the work you’re doing - getting to know yourself, changing your inner voice, showing up differently…it matters.

Every time you pause, reframe, speak up, or give yourself grace, you’re planting something your kids will grow up standing on.

I was raised Catholic, in a small town where conformity was currency and silence often felt safer than truth. Like many queer kids, I learned how to hide early. I became good at shape-shifting—adjusting my tone, posture, even my dreams—just to feel a little less different.

I was also adopted. And while I was lucky to grow up in a loving home, there was always this quiet, lingering question beneath the surface: Where do I truly belong? That question followed me into adulthood. I tried to answer it with achievement, with approval, with striving. None of it worked for long.

When I came out in my 30s—to myself, and then to the world—it was a moment of truth and tremble. Some people wrapped me in warmth. Others vanished without a word. In the 18 months that followed, I lost over 60% of my clients. But strangely, I felt lighter. For the first time, I wasn’t hiding anymore.

I live with ADHD. That means I experience the world differently—intensely, unpredictably, often beautifully. My brain connects dots others don’t. It pushes me to dream big, move quickly, feel deeply. But it’s also brought exhaustion, anxiety, and more than a few internal battles. The same mind that fuels creativity can also spiral into self-doubt.

I’ve had big wins. I’ve helped raise millions for causes I believe in. I’ve worked with global leaders. But none of those moments were mine alone. I’ve been supported every step of the way—by mentors who believed in me, teammates who showed up, and friends who reminded me to breathe. I’ve also had my fair share of big failures. Some of them quiet. Some loud. All of them humbling.

And through it all, I’ve learned: what matters most isn’t whether you’re on a mountain or in a valley. It’s what you take with you when you leave. Every success and every struggle is a teacher, if you let it be.

For years, I wore success like armor. I pushed through pain. Smiled when I was falling apart. I told people I was “fine” while quietly crumbling. I thought if I just achieved enough, I’d finally feel worthy. But chasing worthiness is a losing game.

The real shift began slowly. In therapy. In conversations with people who didn’t ask me to shrink. In the soft spaces of community. That’s when I stopped trying to “fix” myself and started learning how to live—really live—with all of who I am.

Yes, I’m queer.

Yes, I’m neurodivergent.

Yes, I’ve struggled—with both unexpected physical and mental health, with shame, with feeling like I didn’t belong.

Yes, I’m adopted.

And yes—I’m still here. Still curious. Still trying. Still grateful.

I don’t have all the answers. But I do know this:

You are not broken.

You are not too much.

You are not behind.

You are allowed to rest. To be loved. To be seen. To take up space.

Unleash your authentic, creative, playful, multipassionate self.

"Let joy be your gps" - Robin Sharma

You deserve to go where people’s eyes light up when they see you coming. You deserve to feel safe in your own skin. You deserve to dream—boldly, messily, beautifully—and know that your dreams matter.

And if no one’s told you this lately: You are worthy of the life you imagine. Even now. Especially now.

So whether you’re on your way up or finding your footing again, trust that both places can be sacred. Learn the right lessons from both. And when in doubt, remember: your story isn’t over.

I’m not done writing mine.

And maybe, just maybe, your next chapter is the one that changes everything.

Listen to your intuition. Trust your instinct. Follow Your Heart. Let your rainbow shine.

Thrive forward.

Friendship and community are important to everyone, but may be of crucial importance to those who have felt isolated or excluded, a common experience for people with ADHD. In research, ADHD in children and adolescents has been related to a host of social challenges, with higher bullying victimization rates, more peer rejection, and higher conflict relationships. In adulthood, many individuals with ADHD have difficulty maintaining friendships and experience challenges with romantic relationships. Taken together, this paints a grim picture, suggesting that if you have ADHD, you cannot have fulfilling relationships. As someone with ADHD and a researcher in this field, I rarely see literature on how ADHD can contribute to meaningful, uplifting friendships. However, I believe that although ADHD can present challenges to your social life sometimes, it can also make you a caring and empathetic friend and partner, especially when you find the right people.

My experiences

As a child, I definitely experienced these social challenges, always feeling out of sync with my peers. At that time, I had no idea why I felt different from a lot of my peers and struggled to connect with them. As I got older, I learned to mask who I was to try and fit in a bit more. Without really thinking, I studied how other people acted and mimicked that. Sometimes I would slip up by getting too excited about something, interrupting others, or being too loud. For me, each stage of education got a little better socially, however, everything really changed for the better when I got to university.

When I got to university, I had an opportunity to reinvent myself now that I was being exposed to new people. I no longer had to hide my love for learning like I did as a teen. I quickly became friends with people in my classes, with whom I shared many interests outside of school. In my first year, my uncle who I was very close with passed after a long battle with cancer and it was a defining moment in many of my friendships. My new friends were at my side, comforting me, giving me notes I missed, and helping me catch up on assignments. My high school friends were less than helpful, and I decided to start to put some distance between us. I had believed that I wouldn’t find better friends, but this experience helped me to believe that I deserved more.

My new friends were largely neurodivergent with some being diagnosed and undiagnosed, maybe not surprising for an undergrad neuroscience program. For the first time, I really feel like I fit in and had found my community. My “weird quirks” were just a part of me and not judged. My best friend in my program was my study buddy as we shared the same requirements before exams and often stuck together. Our routine for exams was to stop

studying at least 2 hours before, eat a good amount of food, and chat in a relaxed environment. Years later, I found out that he was diagnosed with autism when he was younger. Later in grad school, I bonded with friends over info-dumping and body doubling (work on a task next to someone to help with focus and accountability).

I reconnected with a friend from high school, and she remarked how much more confident and happier I seemed to be after undergrad. I was much more self-assured and worried a lot less about what people thought of me. I finally was able to be myself around people who cared about me.

Now in my late 20s, I see many of my closest friends are neurodivergent. We support each other through humor and shared understanding—joking about ADHD-related lateness or lost keys while also offering real support when needed. These friendships have been invaluable, not despite our differences, but often because of them.

Importance of a neurodivergent community

I have often been described as friendly and outgoing, so I have found making friends to be pretty easy, but maintaining friendships was another story. I had a hard time remembering to make plans, keeping up with constant communication, and disliked exchanging pleasantries when I just wanted to launch into a conversation. With my neurodivergent friends, I have found that our communication styles align, and even if we don’t see each other for a while, it is like no time has passed when we do reconnect. I don’t feel the same need to overexplain myself, because they just understand.

In an interview study I conducted, many people remarked how they believe that having ADHD has made them more empathetic and understanding of other people. When someone was having a bad day and took it out on them, they viewed it more as that person needing support than taking it personally. Others mentioned that they were curious and had a wide range of interests, which helped them have conversations with many different people. Unfortunately, everyone reported experiencing stigma.

Overall, having a neurodivergent community can be beneficial for people with ADHD, whether it is a group of in-person friends or an online community. Often the expectation is put on people with ADHD to change themselves to be better liked. Improving self- and emotional-regulation abilities can be beneficial, but the burden of adapting shouldn’t fall solely on neurodivergent people. Additionally, neurotypical people should be educated to be less judgmental and more accepting of neurodiverse individuals. There are countless things that neurotypical people do that can be irritating or rude to neurodivergent people, yet our society expects neurodivergent people to put up with it. One of the biggest beauties

of life is how everyone is a little bit different, and I think that understanding that and having an accepting community can do wonders for everyone.

The ADHD brain is one of great extremes—referred to as both a curse and a superpower. One minute, you can't focus on anything; the next, you're locked into hyperfocus and can't break away. You feel unmotivated and uninterested—until something ignites your curiosity and you're consumed by it. It's the child who struggles in school, but grows into the entrepreneur who changes an industry. The adult who gets overwhelmed at the grocery store, but envisions connections no one else can see. It's a brain built for bursts of brilliance—but it's constantly coming up short in a world that celebrates consistency and linear thinking.

The dual nature of ADHD has long divided our community, sparking debate among researchers, clinicians, and lived-experience voices alike. For some—like the well-known Dr. Russell Barkley—ADHD is a neurological disorder with serious, chronic impairments that are deeply disabling. According to him, calling it a superpower risks undermining decades of advocacy aimed at securing accommodations and recognition. And honestly? On the days I find myself lying on the floor having my third meltdown of the week (deeply short on sleep because my dopamine hungry brain had me scrolling on my phone until 2 AM), acknowledging that I have a disability brings a sense of relief. It helps me understand that my struggles are valid and not simply a result of personal inadequacy.

But I also have days when I admire this brain. Her curiosity. Her rebellious spirit. Her refusal to grind for things that don’t matter. For all the times I’ve been late, for all the emails I’ve missed, I sometimes catch my own unimpressed reflection and wonder: maybe my sense of time isn’t broken. Maybe that immersive daydream—the one I reluctantly tore myself away from—mattered more than the scheduled teeth cleaning. Somewhere underneath all the hard days—all the ones where I feel incompetent and frustrated by my nonlinear mind—I can’t shake the feeling that this chaos is leading somewhere meaningful. That this brain might help the world in ways I don’t yet fully understand.

It’s in these moments that I understand where the other side is coming from. I feel a quiet frustration rise—not just at my own struggle, but at the world around me. A world so focused on diagnosis, so invested in defining one kind of brain as the gold standard. A society that prizes linear thinking, predictability, and productivity—and teaches us, often subtly, to measure ourselves against those ideals. We try to fit the mold. We put in more effort. But ironically, the harder we work to become what the world expects, the further we drift from our own strengths—and the less able we feel.

While the debate surrounding ADHD's nature – whether it's a disorder or the result of an evolutionary mismatch – is captivating and often stirs emotions, it's not the debate I’m interested in today (for the record, my official stance is that each ADHDer should use the language they find most empowering – and yes, that is allowed to change from moment to moment while we wait for scientific consensus).

Whether you embrace the term 'disability' or find comfort in the ideals of neurodiversity, an ADHD diagnosis allows us to attribute our difficulties to something beyond our individual shortcomings. And for those of us diagnosed as adults, this is the first step in healing what I call the ‘ADHD Shadow’ – the painful internal narrative that forms before diagnosis—when years of struggle are misattributed to personal failings rather than neurobiological differences.

In my own blog, The ADHD Awakening, I’ve explored how the stories we carry about ourselves don’t just explain our present reality—they shape it. That’s why changing those stories isn’t just helpful—it’s mission-critical. If we don’t, we risk staying stuck, living out a future written by our past.

But foundational to changing that inner narrative is something even more overlooked: changing the expectations we hold for ourselves.

In my experience—and in so many others’—this part often gets missed. We get a diagnosis, maybe try a medication or two, and then carry on with life, now with a label. But the pressure to function like everyone else? That stays. And when we inevitably fall short, we tend to meet ourselves with the same old message:

Whether you see your ADHD as a disability or a difference, the reality is this: you are living in a world that places expectations on you that don’t match your capacity to meet them. That mismatch? That’s called ableism. And after decades of living inside that system, we start to internalize its messages—absorbing those expectations and mistaking them for our own. That’s called internalized ableism — the process of taking society’s biases and turning them inward, often without even realizing it. It’s the shame-filled voice that whispers, “I should be able to do this.”

So the next time you hear yourself say the word “should,” I want you to pause—and choose the metaphor that speaks to you most.

Picture an orchid that looks like it’s dying a little. (Don’t worry—this ends well.)

Drooping leaves, stunted blooms, a stem that looks like it’s giving up. But here’s the thing about orchids: they aren’t like other plants. They need specific conditions to thrive—indirect light, just the right humidity, and a careful balance of space and care.

They may seem finicky, but when those needs are met? They’ll outlast and outshine every plant in the room.

If it wasn’t clear: you are the orchid. And can we all agree that the solution isn’t for the orchid to try harder?

Would you expect someone with less than 20/20 vision to try harder to see? Of course not—you’d hand them glasses.

ADHD is no different. It might be invisible, but its impact is real—on focus, memory, energy, and emotion. Clinicians and governments recognize it as a disability for a reason.

If that’s the lens that helps you understand your experience, you deserve support. You’re not asking for special treatment. You’re asking for tools that fit your brain

And for the love of all that is good, please—stop trying harder!

Laura Hudson is a writer, ADHD educator, and advocate with both lived experience and professional expertise in adult ADHD. She specializes in supporting individuals diagnosed later in life—helping them untangle internalized shame, understand their unique neurobiology, and build ADHD-friendly systems for thriving. Laura is also passionate about working with individuals who struggle with Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviours (BFRBs), such as hair-pulling, skin-picking, and nail-biting.

She is currently training as an ADHD coach and is the creator of The ADHD Awakening, a blog dedicated to demystifying ADHD, challenging pathologizing narratives, and equipping readers with practical, evidence-based strategies for self-understanding and growth.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is more than just a medical diagnosis; it's a lived experience that affects millions of people worldwide. Yet, despite its prevalence, misconceptions and social stigma often overshadow the reality of those living with it. By delving into the sociological aspects of labeling and social myths, we can better understand the struggles individuals with ADHD face and explore ways to support them in thriving.

Unpacking ADHD Through a Sociological Lens

ADHD is commonly associated with inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. However, these

symptoms manifest differently from person to person, leading to misjudgements and misdiagnoses.

From a sociological perspective, the labels and myths attached to ADHD can significantly impact an individual's self-esteem and social standing. Research shows that being labeled as “hyperactive” or a “troublemaker” often leads to negative perceptions from teachers, peers, and employers (Metzger & Hamilton, 2020). These stereotypes can create a cycle of marginalization, making it harder for individuals to access support and achieve their potential.

The Emotional and Social Toll

Imagine constantly being told you're not trying hard enough or that your struggles are due to

laziness. For individuals with ADHD, these misconceptions are all too common. The emotional toll of feeling misunderstood can lead to anxiety, depression, and feelings of inadequacy. Studies indicate that people with ADHD often adopt maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance, which can further exacerbate stress and impair daily functioning (Koehler et al., 2021).

However, positive coping strategies, like seeking social support and breaking tasks into manageable steps, have been shown to improve outcomes.

Shifting the Narrative

Breaking the stigma around ADHD requires education and empathy. By promoting awareness of the neurological basis of the condition, we can challenge harmful myths and foster more inclusive environments. For instance, creating supportive learning spaces and flexible work environments allows individuals with ADHD to leverage their creativity and problem-solving abilities. Moreover, building strong support networks with family, friends, and mental health professionals can empower individuals to advocate for their needs and thrive.

Practical Strategies for Coping and Thriving

Conclusion

ADHD is not a one-size-fits-all condition. By recognizing the profound impact of social labeling and myths, we can better support individuals in managing their symptoms and reaching their full potential. Through empathy, education, and practical support, we can create a more inclusive and understanding society where individuals with ADHD are not defined by their diagnosis but celebrated for their unique strengths.

References

Gormley, M. J., & Lopez, F. G. (2020). Coping strategies among adults with ADHD: The mediational role of attachment patterns. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(5), 693–703.https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718770012Koehler, C., Schredl, M., & Vetter, V. R. (2021).

The role of stress coping strategies for life impairments in ADHD. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 679832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.679832Metzger, I., & Hamilton, L. (2020).

The stigma of ADHD: Teacher ratings of labeled students.Sociological Perspectives, 63(4), 609–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121420937739

You may be wondering how I went from being an ADHD parent to also being an ADHD advocate.

The first two decades of my career taught me that I could not be an advocate for anyone, on any matter, if I did not first understand and fully appreciate the interconnectedness of trauma, shame and systemic failure.

Consider Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps The Score, “…four fundamental truths: (1) our capacity to destroy one another is matched by our capacity to heal one another. Restoring relationships and community is central to restoring well-being; (2) language gives us the power to change ourselves and others by communicating our experiences, helping us to define what we know, and finding a common sense of meaning; (3) we have the ability to regulate our own physiology, including some of the so-called involuntary functions of the body and brain, through such basic activities as breathing, moving, and touching; and (4) we can change social conditions to create environments in which children and adults can feel safe and where they can thrive (2015, 38).

With the above in mind, imagine the trauma inflicted on parents when professionals and institutions blame them for their child’s reactions. This blame denies the safety required for vulnerable communication. The parents will feel powerless and helpless as they are held solely responsible for what they cannot control and do not fully understand. They are denied the support they so desperately need. They fight, flee, or freeze.

I am one of these parents. I came to the school asking to be part of their community, seeking their help. They abandoned me.

Now, consider the trauma inflicted on a child when the adults in their life blame them for the dysregulation they cannot control. The child has no choice but to assume they are the problem. They fall victim to an environment they have no control over. They feel powerless and helpless. They fight, flee, or freeze.

So where to we go from here?

I have learned that advocacy is one of the tools that can help to dismantle discrimination, stigmatization, ignorance and the misuse of power and authority. Making my ADHD advocacy public denies the opportunity for our experience to be weaponized against us and instead allows us to focus on healing.

Before our personal details are revealed, I want to tell you more about the person behind these words.

I am 49 as I write this. I live in Peterborough, Ontario, but I was born and raised in Hamilton. We moved to Peterborough when our oldest was five years old and our twins were three and a half. I never thought I would live here, and I had never spent any time here. Funny how quickly everything can change. My husband was going to be transferred, and Peterborough was one of the options. We drove up one afternoon, spent the night, puttered about the city, and said, “Yeah, OK, we can make this work.” Within three months, we bought a new house, sold our old house, and moved to Peterborough. This was a huge transition. I did not know a single person living here. None of us did. It worked out.

Prior to moving to Peterborough, I had been working as a social worker for many years. At different points in time I worked within the Hamilton emergency shelter system, child welfare, and inpatient psychiatry.

Since living in Peterborough, I have gained additional experience. I worked in community mental health, hospital settings, home care, and hospice. I also returned to school and earned my MSW. It took me four years to accomplish this, taking one course at a time. I am very proud of this achievement. As soon as I earned my MSW, I opened up my private practice, which is what I do now.

Needless to say, I have more than two decades of experience working as a social worker. Most of this experience occurred within our government systems, as a case manager, advocate, program manager, and therapist. I love what I do and feel very honoured and committed to continuing. I also want to share that I chose to do my MSW at Dalhousie University for its focus on social justice.

Are you starting to understand why my personal life and professional life started to merge?

I did not seek or plan to be an ADHD advocate; it was inevitable.

I know how to be a social worker, an advocate, and an activist. It is wild to say, but I have more experience in years as a social worker than I do as a parent. Despite this, I was not prepared for the resistance I encountered from the school system. Nor did I expect it to get so personal.

I have never confronted a system so desperate to remain the same despite advances in research, knowledge, and best practices. I have never faced an essential service that impacted the lives of so many people, that held so much power, with little to no accountability. I don’t know about you, but I know of no examples of positive outcomes born from those who hold incredible power and influence without accountability. I know of many instances where these factors have been causal to atrocities.

We need to worry about this.

It is no wonder that students, their families, and the professionals working within this system are not well. Moral injury and trauma are being inflicted without consequence, question, or a genuine effort or desire for it to be different. Narratives are being manipulated and dominated by the same well-funded voices. The government blames the boards, the teachers, and the unions. The teachers blame the government, boards, and parents. The unions blame the government and promote the victimhood of teachers. Research and news articles mostly focus on poor student behaviour. Few articles are printed or trend when they talk about the experience of students and families. We would much rather view teachers as the Mary Poppins-like figures of our communities, the governments as never doing enough, and the students through the lens of “there’s something wrong with kids today.”

Too many adults blame children and youth with little to no critical thought of their role in shaping these kids. While attempting to collaborate with the adult professionals working within the schools, I noticed that most of them did not have the regulatory skills they expected the kids to have.

Witnessing the trauma inflicted on our ADHD youth strengthened the ADHD advocate in me.

“You’re lazy,” “try harder,” “focus,” “sit still,” “you need to see a doctor,” “you will amount to nothing,” “let’s see who gets further in life,” “you have no friends,” “no one likes you,” “you’re going to live in your parents’ basement,” “live off your dad’s money.”

That is but a small sample of what my kids, primarily my daughter, heard day in and day out from the adult professionals who were supposed to be teaching them, mentoring them, and modelling the skills they were expected to develop.

I can prove it, too. I have receipts.

Your ADHD Advocate,

Lynn